Everything you need to be a published author—all in one place.

Publishing

eBooks

Audiobooks

Editing

Cover Design

Marketing

Your full-service book publishing partner

Outskirts Press helps authors develop, publish, and market high-quality, award-winning books featuring...

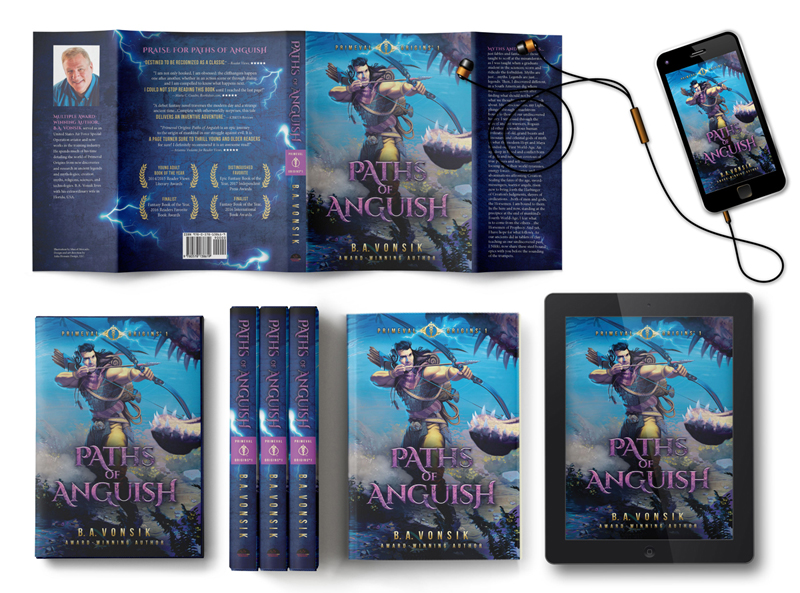

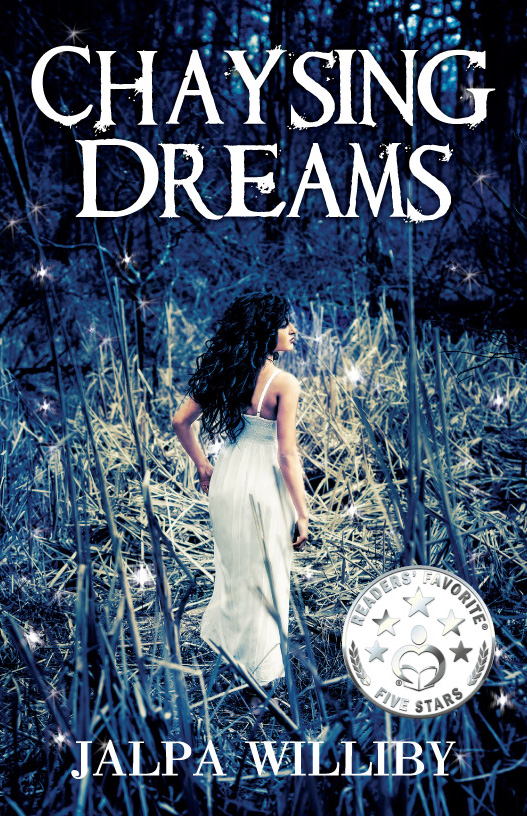

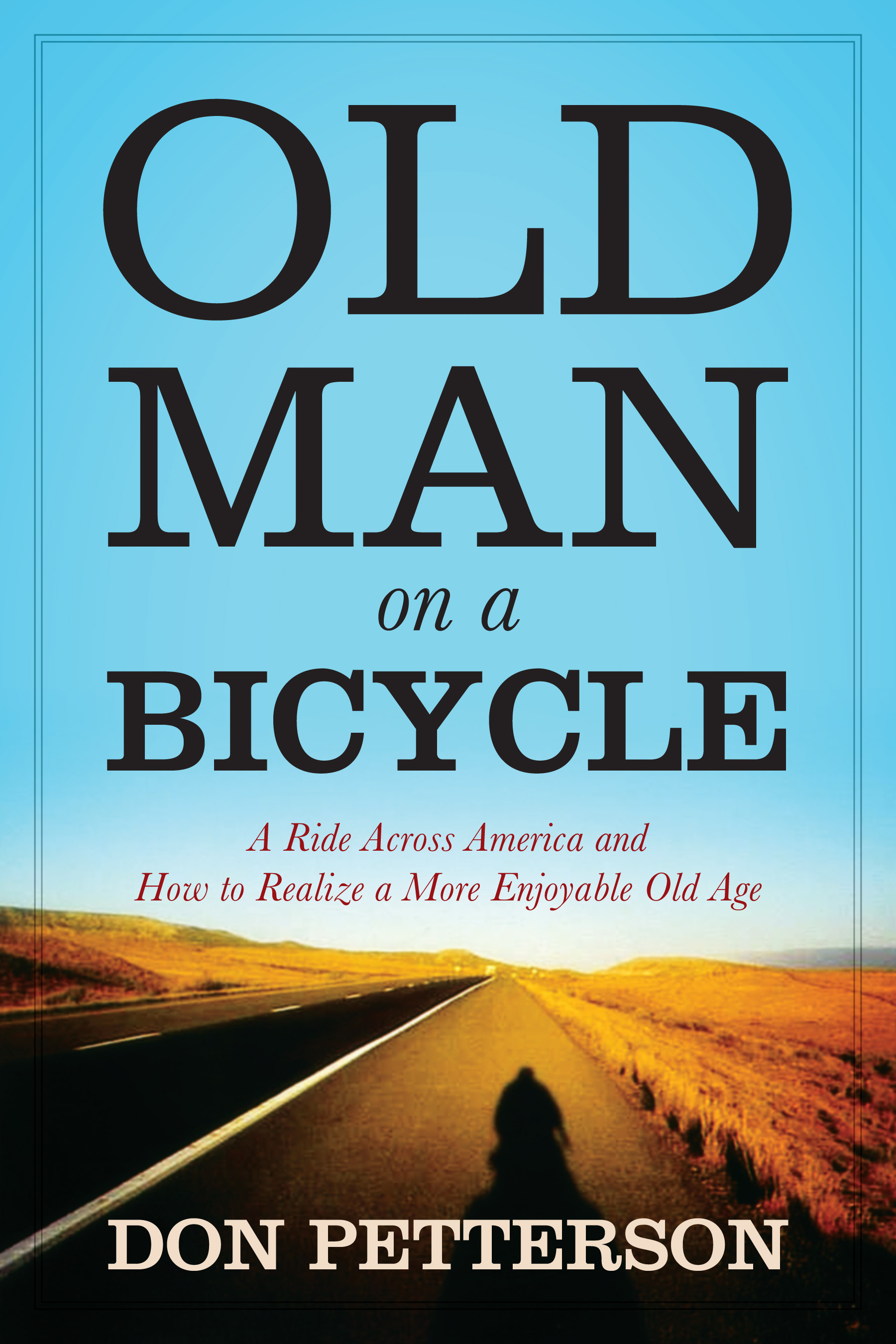

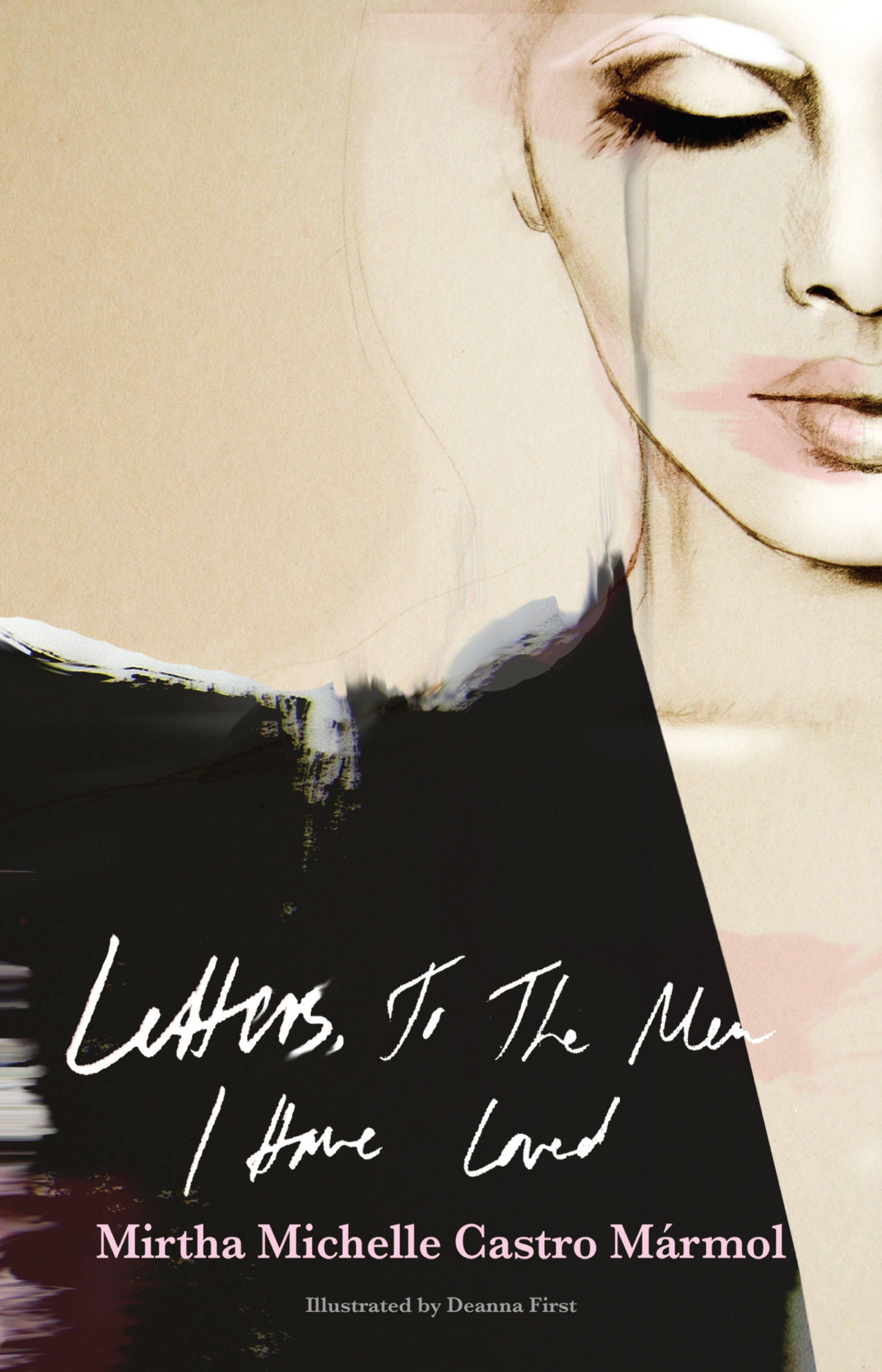

- Exceptional cover design

- Professional book layout & design

- High-quality printing

- Paperback, hardback, eBook, & audiobook editions

- Unlimited worldwide distribution

- Extensive book marketing services

- And more...

We take the work out of self-publishing and deliver industry-leading service at an affordable price.

You keep all of your rights and royalties.

Explore our publishing services and recommendations for your book genre...

From trim sizes to formats, illustrations to stock imagery, custom formatting to indexing, our genre pages are designed to highlight those offerings and services that are most applicable to your book's specific genre, showcase examples from our published authors and offer you a different way to explore your publishing journey.